|

The following is from a lecture by Preston Manning, president of the

Manning Centre for Building Democracy. It was presented in Ottawa last

February at a seminar on ‘Navigating the Faith/Political

Interface.’ Manning notes that much of his information was obtained

from Adam Hochschild’s Bury the Chains (Houghton Mifflin, 2005). The following is from a lecture by Preston Manning, president of the

Manning Centre for Building Democracy. It was presented in Ottawa last

February at a seminar on ‘Navigating the Faith/Political

Interface.’ Manning notes that much of his information was obtained

from Adam Hochschild’s Bury the Chains (Houghton Mifflin, 2005).

MANY lessons can be learned from a notable

faith-oriented campaign which achieved a great social good: the

emancipation of slaves within the British Empire.

Use the law

Use the existing law, imperfect as it is, to the

maximum extent possible to advance your cause.

The first round against slavery was fought in the legal

arena in the late 18th century. It was spearheaded by Granville Sharp, a

committed Christian (Anglican) who held a minor post in the ordinance

office in the Tower of London. He arranged for the legal defence of James

Somerset, an escaped slave whose former owner was trying to recapture him.

Sharp argued forcibly that the British law allowed no

one to be a slave in England itself.

Lord Chief Justice Mansfield’s carefully worded

ruling set Somerset at liberty without automatically freeing other slaves.

But almost everyone, including many lower court judges, believed Mansfield

had indeed outlawed slavery in England.

Christians should follow Sharp’s example, and use

the current laws. We should also use the Canadian Charter of Rights and

Freedoms, not just criticize the Charter.

Publicize suffering

|

| Christian anti-slavery campaigner and politician

William Wilberforce |

Begin your initiative not by moralizing, but by

identifying and publicizing the suffering that the violation of your

principles/ethics creates.

The suffering of slaves in transit across the Atlantic

was illustrated by the Zong case in 1783. The case concerned a slave ship

whose captain threw 136 slaves into the sea, and whose owners filed an

insurance claim for the value of the dead slaves.

The case came up before Lord Mansfield. Granville Sharp

attempted to turn it into a homicide trial, not a civil insurance dispute.

The case illustrates the point that if you’re going to crusade

against an evil, make a start by identifying with the suffering that it

causes – rather than with abstract principles and points of

law.

The Zong case produced no legal victory –

but as Adam Hochschild writes, it provided a “horror

story” to stir public sentiment.

Immediate objectives

Distinguish between your immediate objective and your

ultimate objective – and proceed incrementally, rather than

taking an all-or-nothing approach. Hochschild notes the

abolitionists’ decision to make the immediate objective one of

abolishing the slave ‘trade’ rather than slavery itself.

Hochschild recommends that activists “legitimate

the discussion” of their issues in public and political arenas where

it is still taboo. One way to do this is by proposing an innocuous rather

than provocative introductory resolution.

A good example is MP William Wilberforce’s

initial resolution “that the House will, early in the next session,

proceed to take into consideration the circumstances of the slave

trade.”

It is also helpful to be inclusive rather than

accusatory in your language, in describing the evil to be remedied. In his

introductory speech on his slave-trade resolution, Wilberforce declared:

“I mean not to accuse anyone, but to take the shame upon myself, in

common, indeed, with the whole Parliament of Great Britain, for having

suffered this horrid trade to be carried on under their authority. We are

all guilty – we ought all to plead guilty, and not to exculpate

ourselves by throwing the blame on others.”

Improve language

|

| Starting at Vancouver’s First United Church, the

21st annual Good Friday Stations of the Cross made stops at landmarks such

as Canada Place and The Women’s Centre. These contemporary

‘stations’ were designated as “cross-sections of the

struggles of justice and evil over the course of the last year.” The

event ended at the 2010 Olympic Clock – which was renamed the

‘Homelessness Action Clock.’ Photo: Al McKay |

Change your language, if necessary, to suitably present

the issue. Thomas Clarkson (a divinity student and committed evangelical)

won a 1785 essay contest, which asked the question: “Is it lawful to

make slaves of others against their will?”

He became the apostle Paul of the anti-slavery

movement; without Clarkson there would have been no movement.

Quaker abolitionists undertook to publish his essay in

1786. This demonstrated the importance of finding the right language.

One of the things which hampered the Quakers’ crusade against

slavery was that they spoke and wrote differently than most other

Englishmen – using “thee” and “thou”

and other quaint phrases.

Clarkson and Granville Sharp (who were not Quakers)

changed the language of the campaign, improving on the archaic language of

the Quaker abolitionists.

Embody the cause

Find articulate spokesmen who literally

‘embody’ your cause.

A freed slave became a striking and articulate public

advocate of abolition of the trade. Olaudah Equiano published his

biography, and went on a great political book tour.

Nothing is more useful to a cause than a person who

seems to embody it. Ask yourself: “Out of whose mouth would our

message be most credible?”

Attack myths

Identify and attack the ‘myths’ which

sustain the status quo and opposition to change.

One of the myths which sustained the slave trade was

the idea that it provided, as Hochschild puts it, a “useful nursery

for British seamen.”

The abolitionists attacked the falsehood that the slave

trade somehow was a good training ground for sailors; in actuality, 20

percent of the crews of slave ships died on their voyages.

Continue article >>

|

Utilize democracy

|

| Quaker Elizabeth Fry spearheaded the movement for prison reform in Britain. |

Utilize the tools which democracy, however flawed,

gives you. The anti-slavery advocates used freedom of speech and the

freedom to petition Parliament, even though most of the British population

at the time did not yet enjoy the vote.

The anti-slave-trade committee pioneered several tools

used by civic organizations today:

• Direct-mail fundraising and pamphleteering.

• Striking symbolism, utilizing Wedgewood’s

special line of china showing a kneeling African with chains uplifted and

beseechingly asking, ‘Am I not a man and a brother?’

• Petitioning of Parliament. By 1788, petitions for

abolition or reform of the slave trade had been signed by between 60,000

and 100,000 people.

• Impressive spokespersons, such as ‘Amazing

Grace’ writer John Newton, a reformed slave ship captain.

• Giving voice to the victims: such as Quobna Ottobah

Cugoano, another freed slave who published a book.

Invent tools

|

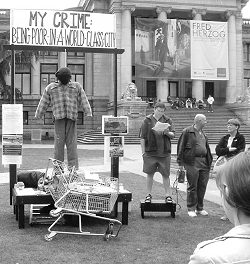

| This display was the centrepiece of a vigil conducted

by Streams of Justice at the Vancouver Art Gallery on Good Friday.

The following day, participants returned to make a more positive

statement, according to organizer Dave Diewert. “We used the gallows,

without the rope or hanging man, as a space for kids to draw pictures of a

new reality. It was an enactment of turning swords into

ploughshares.” Photo: Al McKay |

Invent new tools to advance your cause. Abolitionists

discovered a new tactic: the boycott.

The British public started to boycott sugar from the

slave-oriented West Indies, in favour of sugar from India. The boycott was

such a novel idea that the very word would not come into the language for

nearly another century.

At a time when only a small fraction of the population

could vote, citizens took upon themselves the power to act when Parliament

would not. The boycott was essentially the work of women.

Endure setbacks

Be prepared to suffer, and endure major and

discouraging setbacks. In the case of the Society for Effecting the

Abolition of the Slave Trade, these included:

• The insanity of the King, which brought parliament to

a standstill.

• Slave revolts in the Caribbean, which produced fear

and a counter-reaction.

• The French Revolution, which originally raised hopes

– and then dashed them.

• The insidious influences of the

‘gradualists’ in Parliament – who did not oppose

the abolition of the slave trade, but only advocated that it be done

‘gradually.’ As a result, the public wearied of the debate.

• The dominance of the House of Lords, which was

generally hostile to abolition.

• The war with France, which brought all democratic and

social reform in Britain to a grinding halt.

• The lack of a good strategist in Parliament –

which led to Wilberforce’s bills being defeated time and time

again.

Divide opposition

Find a strategy that divides the opposition to your

reform.

The anti-slavery campaign found its much-needed

strategist in James Stephen. One of the Empire’s leading maritime

lawyers, and a prominent authority on international law, he had a visceral

hatred of slavery – born of living in the West Indies.

He devised the strategy of calling for the abolition of

the slave trade with the French at a time when England was at war with

France.

He decided to appeal not to the conscience of the

British parliamentarians but to their prudence – arguing that

abolition was a wise and expedient thing to do.

Stephen called on Wilberforce to draft a bill which

banned British subjects, shipyards, outfitters and insurers from

participating in the slave trade to the colonies of France and its allies.

This linked slavery to the war effort, and split the pro-slavery lobby. The

foreign slave trade act sailed through the House of Commons with surprising

ease – and the bill passed in the House of Lords.

Shift arenas

If you can’t get a favourable decision for your

cause in one arena (e.g. the House of Lords), shift the decision to another

arena (e.g. the House of Commons) where you can get a favourable decision

– and do everything to support reforms which strengthen that

decision-making arena.

The moral/social reformers who opposed slavery made

common cause with the parliamentary reform movement in Britain. The fate of

slavery ultimately depended on whether Parliament would pass the great

Reform Bill in 1831. Thus, moving the decision-making to a chamber more

susceptible to public opinion was a key factor in the anti-slavery

campaign.

The Reform Bill passed Parliament in 1832 –

greatly strengthening the House of Commons vis-à-vis the House

of Lords, and making it more susceptible to public pressure.

Final victory

The Emancipation Bill, completely abolishing slavery

throughout the British Empire, passed both houses of Parliament in the

summer of 1833.

The real victory came August 1, 1838, when nearly

800,000 black men, women and children throughout the British Empire became

officially free. By then, of the 12 men who had been part of the original

committee, only Thomas Clarkson was still alive.

A faith-oriented campaign to eradicate a great social

evil and achieve a great social good – freedom for hundreds of

thousands of blacks – was successful. This was largely because

it was conducted by people operating with the wisdom of serpents and the

graciousness of doves, at the interface of faith and politics. Canadians

who want to conduct such campaigns – to eradicate the social

evils of our time and advance social goods – should study this

campaign backward and forward, until they are able to learn and practice

its lessons.

May 2007

|