|

By Frank Stirk

|

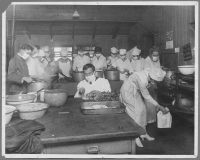

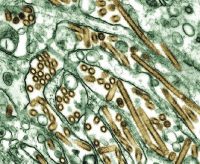

| Volunteers cook food in San Jose, California, during the devastating 1918 Spanish Flu catastrophe. Elsewhere on this page are scenes from the 2004 Avian Flu pandemic. |

CHURCHES can expect to be approached by government and

health authorities for help in coping with what most experts believe is the

certainty of a global and potentially catastrophic influenza pandemic that

could break out at any time.

“It would be nice to respond in the affirmative

– ‘Sure, we’ll help’ – instead of saying,

‘We’re too scared,’” says Dr. Tim Foggin, a Burnaby

family physician and a Christian who sees in this coming crisis an

unparalleled opportunity for churches to show the love of Christ in their

communities.

Foggin moderates an email group dedicated to helping

churches prepare for a pandemic, and co-authored a new Church

Preparedness Checklist with a specific focus on the next pandemic.

Alarm

What has governments, healthcare professionals,

scientists and economists so alarmed is that the world could soon

experience an avian (H5N1) flu pandemic that would make the death toll from

the 2005 tsunami pale by comparison. What has governments, healthcare professionals,

scientists and economists so alarmed is that the world could soon

experience an avian (H5N1) flu pandemic that would make the death toll from

the 2005 tsunami pale by comparison.

“We’re talking 10 times bigger. Two to

seven million [deaths] is usually the ballpark figure,” says Foggin.

“What happens in a pandemic is there’s a

major [genetic] shift in the virus,” says Dr. Eric Young,

B.C.’s deputy provincial health officer. “Our immune systems

don’t recognize that because it’s new. That’s why

there’s no immunity developed in the population.”

“The saving grace so far,” he adds,

“has been that the H5N1 strain hasn’t been easily spread from

person to person. But it’s been pretty virulent when it has gotten

into a person. The mortality rate’s been pretty high.”

For several centuries now, flu pandemics have broken

out every 10 to 40 years with varying degrees of virulence. Some, as in

1957 and 1968, can be relatively minor, and pose about the same threat as

the annual flu outbreak.

But others can be extremely dangerous – the most

recent being the ‘Spanish flu’ pandemic of 1918 -19 which

claimed somewhere between 20 and 40 million lives worldwide, including

50,000 in Canada.

Waves

And unlike other natural disasters, pandemics can

typically last more than a year, striking in waves sometimes months apart.

Each wave can last upwards of six to eight weeks, affecting an estimated 15

to 35 per cent of the population to some degree. And unlike other natural disasters, pandemics can

typically last more than a year, striking in waves sometimes months apart.

Each wave can last upwards of six to eight weeks, affecting an estimated 15

to 35 per cent of the population to some degree.

The social impact would be devastating. Ottawa Public

Health, for instance, estimates that if 25 per cent of the city’s

population was affected and the pandemic lasted seven weeks, there could be

roughly 30,000 new cases, 16,000 people seeking medical assessment, 350

hospitalization and 80 deaths each week of the crisis.

In the Greater Vancouver area, says Foggin, “one

local hospital is looking at having one-third of the staff off sick or [at

home] caring for the sick, and one-third redistributed in the communities.

Now they’re down to one-third of their usual staffing – and

expecting, by conservative modeling, a five-times increase in patient

load.”

No segment of society would be immune, as thousands of

workers book off sick, schools are closed, the movement of people and goods

is disrupted, and so on. As well, says Anglican Canon Douglas Graydon, who

chairs a tri-diocesan working group on pandemic preparedness in southern

Ontario: “It would be so comprehensively global there might not

necessarily be resources that can come into your community from

outside.”

Standing in the gap

It is in this gap that churches are being encouraged to

stand. “Faith-based communities can actually do quite a bit,”

says Young. It is in this gap that churches are being encouraged to

stand. “Faith-based communities can actually do quite a bit,”

says Young.

“Some people may be ill in the home without

anyone really knowing about it . . . so helping to keep an eye on your

neighbour is going to be a really important thing during a pandemic. Some

people will need services that are generally provided in regular times like

Meals on Wheels.”

The opportunities to serve can be as varied as the

needs that arise, as long as stringent rules of personal hygiene (such as

frequent hand-washing) and the prohibitions on physical contact (such as

giving someone a hug) are adhered to.

“Try to think outside of the box,” Foggin

advises. “I don’t expect this to be crystallized or formalized

before anything happens. But if we can have a framework or foundation set,

then there’ll be something that can be ramped up fairly

quickly.”

Churches that do get involved, he adds, also need to

let their municipalities know their intentions “just to have that

dialogue, [keep] those channels of communication open.”

Continue article >>

|

Template

A template for pandemic preparedness that

Graydon’s working group has developed and offered to every Anglican

diocese seeks to remind them that, as he says, part of every

Christian’s calling is “to be servants . . . to embrace risk

and to minister during times of anxiety, confusion and

catastrophes.” A template for pandemic preparedness that

Graydon’s working group has developed and offered to every Anglican

diocese seeks to remind them that, as he says, part of every

Christian’s calling is “to be servants . . . to embrace risk

and to minister during times of anxiety, confusion and

catastrophes.”

Also included, says Graydon, “is a checklist that

parishes, dioceses, actually just about anybody, is encouraged to think

their way through, which should begin to answer . . . how do I go about

getting ready for such an event and what do I need to do next.”

“What I would hope for,” says Foggin,

“is in the major urban centres particularly that there’d be a

handful of churches that can start interacting more intentionally along

these lines and thinking this through and making some initial

plans.”

Yet so far, it seems most churches remain skeptical.

“I have gotten comments about how we’re

just not really sure we believe this is a legitimate concern,” says

Graydon.

They are not alone. Some critics, such as American

science journalist Michael Fumento, writing in the National Post in April 2006, argue

that the whole idea of an impending global pandemic betrays “sheer

ignorance of how viruses change.

“There’s no evidence H5N1 is mutating

toward becoming transmissible between humans. . . . Rather, as one mutation

draws the virus closer to human transmissibility, another is as likely to

draw it farther away.”

False fears?

Fumento warns: “The false fears we sow today we

shall reap in the future as public complacency if a monster truly appears

at the door.” Fumento warns: “The false fears we sow today we

shall reap in the future as public complacency if a monster truly appears

at the door.”

While obviously not questioning the imminent threat of

a pandemic, Young is nonetheless confident that B.C., at least, “will

be very well prepared” when it does strike.

“The indications are,” he says, “that

the antivirals for influenza that we do have may well work to some extent

in a pandemic, even if the virus changes. So there is the possibility that

we’ll have a couple of antivirals that will work.”

In addition, Canada will have a guaranteed supply of

antivirals thanks to its ability to produce and stockpile the drugs, says

Young. “We will be one of the few self-sufficient countries to be

able to do that.”

And even if the skeptics are proven right – or

even if the pandemic turns out to be not as disastrous as many fear it will

be – Graydon believes it still makes good common sense for churches

to have some plans in place in the event of an emergency.

“Let’s look upon this preparedness as part

of our community ministry,” he says, “so that if the parish

really wants to embrace something like this, they can be known within their

community as a Christian community that’s there and available and

ready to help out in times of need.”

Leadership

|

| Avian Flu microbes. |

Even so, Glen Klassen, a biology professor at Canadian

Mennonite University (CMU) in Winnipeg, believes if churches are ever to

have pandemic preparedness plans in place, the initiative will have to come

from their denominational leadership.

“Hopefully, we can work from the top down,”

he says. “Bottom up, we need to sort of do the publicity and raise

the awareness of people at the grassroots level. But in terms of actual

preparedness plans and their implementation, we’ll have to depend on

the people at the top.”

Toward that end, CMU will be hosting a Summit June 20

– 21 in partnership with the International Centre for Infectious

Diseases, a federal agency based in Winnipeg, on how faith communities can

effectively respond to a pandemic.

“We’re expecting to get the top people in

each denomination here. It’s not wide open to the public,” says

Klassen.

Whether top-down or bottom-up, what matters for Foggin

is that churches seize the challenge.

“If the church doesn’t stand up, it’s

going to prove itself irrelevant, as many think it is, unfortunately. But

if the church does stand up, there is such great potential.”

In contrast to the tsunami that caught everyone

off-guard, he says, no one – including churches – will have any

excuse for not being ready when the next pandemic sweeps across the globe.

“We’ve seen the wave. It’s coming slowly and we have time

to prepare. But then at the end, it comes real fast.”

“The analogy I use here in Manitoba is of the Red

River Valley flood,” says Klassen.

“I mean, people know there have been floods in

the past and there definitely will be floods in the future. We just

don’t know when and how severe. So we prepare for the worst

case.”

However, he said, referring to the pandemic: “In

this case, it’s like there’s six feet of snow in North Dakota

waiting to come down on us.”

June 2007

|