|

By Jeff Dewsbury

IT'S A STARK reminder of the complexities war. IT'S A STARK reminder of the complexities war.

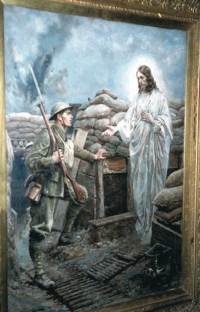

A posting on the Military Christian Fellowship of Canada's website describes the inner turmoil a Christian soldier feels after taking a life in armed combat for the first time. Among other things, the young man is wrestling with the security of his salvation, trying to figure out if the military action has changed his relationship with God.

Matters of the soul

Canada's role in foreign conflicts, particularly in Afghanistan, is continually debated in Parliament - and subsequently at dinner tables and water coolers across the country. But it's the des the deechool te����bates which take place in faith communities - debates that focus on matters of the soul - that pose the toughest questions.

Naturally, evangelicals look to scripture for guidance on the issue. But they come up with different conclusions. The Old Testament contains guidelines for warfare, and there are scores of examples of God's intervention and instruction in combat. Yet Jesus rebuffed Peter for wielding the sword, and cutting off Malchus' ear. He also said "Blessed are the peacemakers." But there are widely divergent views on how peace is 'made.'

While there are no hard statistics on the breakdown between pacifists and 'just war' supporters among Canadian evangelicals, there seems to be a common perception that most think there are times when the use of force is necessary to stop an aggressor.

"Ultimately, pacifism acquiesces in the doing of an injustice," says David Koyzis, a professor of political science at Redeemer University College in Ancaster, Ontario. He points to th��������������������������������e call to pull troops out of Afghanistan as a current example. "Leaving chaos and civil war behind would be unjust."

Koyzis was born in the United States, and can recall a time when he briefly held to pacifism - when conscription for the Vietnam War officially ended just before his 18th birthday.

"I have a great respect for people in the historical peace churches who feel they themselves can't wield the sword," he says. "But I have a problem with those who want the government to lay down the sword." "I have a great respect for people in the historical peace churches who feel they themselves can't wield the sword," he says. "But I have a problem with those who want the government to lay down the sword."

Domestic police forces are a local example which Koyzis believes can be translated to a global scale. "There are going to be criminals who break the law. I would not want to live in a country where police powers were not to be exercised."

But the professor also acknowledges warfare involves more than police action, more than simply the pursuit and apprehension of perpetrators. A declaration of war pits a nation against another - something entirely different.

Just war

'Just war theory,' a body of thought w����hich tries to define when a war is morally acceptable, "recognizes that war itself always unleashes evils on people, in particular innocent civilians," says Koyzis. Making judgments about the United States military in Iraq and Canada's reasons for hitting the ground in Afghanistan, using traditional just war criteria, is tricky. Technically, says Koyzis, both fail to meet just war criteria.

But is Canada actually at war in Afghanistan? Koyzis is not alone in believing the U.S. president's declaration of the 'war on terror' directly after 9/11 has confused the issue.

"The rhetoric at that time was moving toward a dangerous overextension of political power," he laments. "A war on terror? You can't defeat terror any more than you can wage a war on sin."

War and children

For people like Kathy Vandergrift who have witnessed the effects of civil war in Africa, it's easy to cut through the rhetoric. Through her previous role as policy director for World Vision Canada, she has seen ��������������������������������the atrocities of war in northern Uganda. She has also been involved in rehabilitating child soldiers as chair of a multiorganizational working group on children and armed conflict in East Africa.

"Looking at world peace from the view of child protection gives one some urgencies on the issue," she says.

Vandergrift was also part of a committee in the Christian Reformed Church which examined teachings on war and peace. Over the past three years, the denomination wrestled with the new realities of war and what it means to "implement our calling to be peacemakers . . . and to put to the fore our mandate to be peace builders," she says.

Among the many elements of the report was the idea that being agents of justice through policing - on a global scale - is more in line with Christian principles than nations, often motivated by national interests, going to war.

Vandergrift also points out that war today seldom involves traditional armies fighting each other across a recognizable�������������������������������� border, as it was in the first two world wars. This new reality makes traditional just war criteria seem out of date.

With this in mind, the synodical committee explored the issue of the Christian's mandate to protect the innocent - focusing on the perspective of individual responsibility, not on state accountability.

"The individual's right to life is front and centre in this paradigm," says Vandergrift, adding that this line of thinking encourages conflict prevention - such as successful peace envoys in eastern Sudan - because it doesn't limit intervention only to areas where there are "strategic interests," such as natural resources.

Though she would be tagged as a just war adherent, Vandergrift thinks people on both sides of the issue are equally passionate about Jesus' calling to make peace.

"The old polarization about war is not a productive way to think about it," she says. "Taking up arms is still very much a last resort . . . and spending more money on armaments t te�����������������������������han on development is not the right approach . . . We should take strongly the biblical call to be agents of justice and peace builders, by holding [perpetrators] accountable."

Shifting stances

One of the effects of the ongoing debate over current global conflicts seems to be the eroding of traditional denominational stances on the issue. Terry Tiessen, professor emeritus at Providence Bible College in Otterburne, Manitoba, is an associate member rather than a full member of a Mennonite church - because he believes "there are times when loving one's neighbour requires using force to protect against force users."

Tiessen says he was "pleasantly relieved" at the number of people who agreed with his just war stance in an editorial he wrote for The Messenger - the magazine of the Evangelical Mennonite Conference (EMC), a denomination with about 60 congregations in Canada.

But it's exactly this type of support that has the historic peace churches concerned about passing the legacy�������������������������������� of pacifism on to future generations. At a history conference on conscientious objectors held last fall in Winnipeg, the erosion of the historical commitment to pacifism was front and centre, according to reports from the Mennonite Central Committee.

Mennonite church leaders and their congregations may be losing their strong convictions to uphold this founding principle of the Mennonite Church, said Harry Loewen, professor emeritus of Mennonite studies at the University of Winnipeg.

Continue article >>

|

A poll conducted by the EMC last year seems to underscore their concerns. Roughly two-thirds of surveyed members say pacifism shouldn't be a test of membership. One-third say a Christian can serve in the military. And a majority say a Christian can serve as a police officer.

Despite some perceptions that pacifism is waning, Robert Suderman, president of the Mennonite Church Canada, says new members are drawn to their churches because of the denomination's well known historical commitment to nonvi��������������������������������olence.

"I have quite a strong sense that the peace position is considered more and more legitimate by many today," he tells BCCN. "Suspicion of the just war 'answers,' if you will, is stronger than in the past." This doesn't mean people are readily embracing a full pacifist position, however.

Suderman notes there is more openness, among his members today, to considering different levels of pacifism. And he points to Project Ploughshares, an ecumenical Canadian advocacy organization which has been working on a 'right to protection' policy for the United Nations - wherein a limited use of force is acceptable when vulnerable people need to be protected.

'Love your enemies'

"We take very literally Jesus' command to love our enemies - and if you love your enemies, you can't kill them," says Doug Pritchard of Christian Peacemaker Teams, an organization which made headlines last year when three of its members were kidnapped in Iraq. "We take very literally Jesus' command to love our enemies - and if you love your enemies, you can't kill them," says Doug Pritchard of Christian Peacemaker Teams, an organization which made headlines last year when three of its members were kidnapped in Iraq.

He says team members are courageous people who are "trained, discipled and prepared to stand between aggressors and the innocent." And he doesn't soft-peddle his view that Christianity and non-violence are synonymous.

"Just war theory is a heresy put together to justify the continued use of force," he says. "We challenge Christians to put on the full armour of God - and to exhibit the same courage as soldiers every day, but without weapons."

Henry Martens of Abbotsford is one of the veterans whose story was highlighted at the fall history conference. He was 19 years old in 1943 when, as a conscientious objector to the Second World War, he was sent to Patricia Lake, Alberta, to work on a secret government project code-named Habakkuk. The project turned out to be a prototype for a warship constructed out of ice.

"We called it Noah's Ark," laughs Martens, who says he had wanted to go to the battlefield as a member of the Red Cross, but the military said he "had to carry a gun."

Though his Mennonite ba��������������������������������ckground forbade him from taking up arms back then, Martens says he doesn't follow the extreme form of pacifism his ancestors did back in his homeland - where villagers were killed by soldiers as family members looked on.

"If someone were to break into my home, I would do whatever I could to protect my wife and family . . . It would be over my dead body," says the 82 year old.

The issue of taking force against an aggressor - whether in one's living room or in the battle theatre - is as multifaceted as pacifism.

Streams of thought

Religious studies professor Craig Carter of Tyndale University College in Toronto breaks down just war theory into three streams of thought: academic debates in the "ivory towers"; 'patriotic duty' thinking, where we assume "it's not up to the average citizen to decide if war is right or wrong, but it's up to the government - and it will be held accountable"; and discipleship thinking - in which "the lordship of Christ is preserved," and citizens and soldi�������������������������ers look to scripture to determine when fighting may be necessary.

Carter, who considers himself a pacifist and worships at a Baptist church, laments that somewhere around 95 percent of Canadian Christians think of war in terms of patriotic duty.

He believes that's not good enough - that we cannot logically "hold people accountable for war crimes if the moral responsibility lies solely with the state," he says.

While he admits the Canadian military structure doesn't allow a soldier to choose when to fight based on personal religious convictions, he does believe a person's faith supersedes his or her duty to the army.

Carter also refers to the late theologian John Howard Yoder's book Nevertheless: Variations of Christian Pacifism, where the writer outlines 21 different forms of pacifism - to emphasize the diverse roots of non-violence. Carter is author of a book on Yoder, and Yoder also figures in Carter's latest, Rethinking Christ and Culture: A Post-Christendom Perspective.��������������������������������

In Carter's view, Christian pacifism must centre on the sacrifice of Christ, not merely on outside factors. "The person of Jesus is essential . . . My pacifist beliefs are not based on an emotional reaction to violence or an unrealistic optimism in human nature."

Human nature is something Maj. Pierre Bergeron, a chaplain in the Canadian military, sees in spades. He says Canadian soldiers feel secure in the knowledge that they don't get involved in a conflict until diplomatic efforts have been unsuccessful. Yet once those soldiers hit the battle arena, they come face to face with the realities of their occupation.

Spiritual dimension

"Once you face the danger of death, the awareness of the spiritual dimension is heightened," he says, adding: "For some people there is a change, and an openness to the existential questions of life." "Once you face the danger of death, the awareness of the spiritual dimension is heightened," he says, adding: "For some people there is a change, and an openness to the existential questions of life."

But when it comes to doing their jobs, there's no room for debate.

"My purpose as a chaplain is not to determine if a conflict is right or wrong,"�������������������������������� says Bergeron, who has served in Haiti, Bosnia - and, most recently, Afghanistan. "My purpose is to serve the men and women who are involved in the conflict."

One of those men is 29 year old Corporal Don Leblanc who, as part of a reconnaisance platoon in the Canadian infantry, sneaks behind enemy lines for weeks at a time gathering intelligence on foot, under the cover of night.

"I find it a little uncomfortable to clash with one of the Ten Commandments in my job description, which is to close with and destroy the enemy," says Leblanc, who attends a Presbyterian church with his wife and infant daughter.

The young corporal says it's never easy to look down the sight of a weapon at another human being - and he candidly says he has sought the counsel of his pastor over the issue.

But he knows he's been sent to do a job "for the people I love and the country I love." And though he has had debates with total strangers over his choice to be in the military, he says that seeing schools stand wh������������������ere there were once only piles of rock - and also women being free to show their faces in public in Afghanistan - gives him and his comrades a sense of accomplishment.

While evangelicals will continue to debate the methods, such developments are lauded from all corners.

July 2007

|