|

BCCN’s series of faith profiles marking the 150th

anniversary of the founding of the province continues, with the story of

one of the province’s more colourful missionaries. Taken from Canada: Portraits of Faith (Reel

to Real), edited by Michael Clarke.

By Ted Gerk

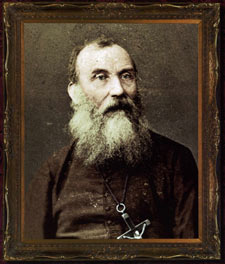

OLD-TIMERS in the Okanagan who knew him well remembered

Father Charles Pandosy as a huge, powerfully built man, capable of amazing

feats of strength, with a big booming voice and a ready wit. OLD-TIMERS in the Okanagan who knew him well remembered

Father Charles Pandosy as a huge, powerfully built man, capable of amazing

feats of strength, with a big booming voice and a ready wit.

Although a deeply religious Oblate missionary, Pandosy

was also known to settle an argument by challenging his opponent to a

fistfight. Today, Pandosy is best remembered as Canada’s Johnny

Appleseed.

Charles John Felix Adolph Pandosy was born in

Marseilles, France, in 1824 to Marguerite Josephine Marie Dallest and

Etienne Charles Henry Pandosy.

His father was a navy captain and a landowner and was

thus able to provide comfortable living conditions and a good education for

his family It was his father’s navy career that drew Pandosy to

the adventure of distant ports.

As a step in this direction, while attending the

Bourbon College at Aries, France, Pandosy decided to enter the Oblate

Juniorate of Lumineres, a seminary for men seeking ordination into the

Oblate Order of priesthood in the Roman Catholic Church. He took his final

religious vows in 1845.

Bishop de Mazenod, founder of the Missionary Oblates of

Mary Immaculate, provided him with an inspiring admonition: “There

are in this world but two loves: the love of God extending to the contempt

of self; and the love of self extending to the contempt of God. All other

loves are but degrees between these two extremes. Do not fear, you obey the

One who rules the world.”

This wisdom would guide Pandosy’s missionary

endeavours in the Pacific Northwest for more than four decades. In

February 1847, the 23 year old Pandosy and four others were sent from

France to the mission fields of the Oregon Territory.

It was an arduous eight-month journey, culminating in

their arrival at Fort Walla Walla. Here, the men began to fulfill the

objective of their journey: the evangelization of the Yakima Indians.

Pandosy and the others quickly discovered the violence

of the region. On November 29, 1847, the Marcus Whitman Massacre took

place, in which several Cayuse Indians killed 13 people and took more than

40 hostages. In February 1848, American troops were dispatched, and the

Cayuse War began. The war was to last two-and a half years.

Motivated by these perilous events, Pandosy’s

superiors allowed for early ordination. Pandosy and a colleague officially

entered the Oblate Order in early January 1848, the first priests ordained

in what was to become Washington State. Pandosy altered his name at this

point to Charles Marie Pandosy.

The missionaries not only cared for the spiritual needs

of the natives, they also served as translators and as peacekeepers.

Pandosy and his co-workers managed to keep the Yakimas from entering the

war. Pandosy became fluent in the Yakima language and eventually

compiled its first dictionary. He later acted as a mediator and an

interpreter between the Yakimas and the white man while continuing his

missionary work among the Indians and serving as an army chaplain.

In March 1859, war flared between the U.S. Army and the

Spokane and Yakima Indians, and the Oblates made the difficult decision to

close their missions among the Yakimas and the Cayuses.

In summer 1859, Pandosy was sent to the Okanagan Valley

in British Columbia, where he established a mission known as L’Anse

au Sable, the Cove of Sand, in an area that is now the City of Kelowna.

Pandosy quickly recognized the agricultural potential of the

Okanagan’s temperate setting and planted its first apple trees,

encouraging new settlers to do the same.

Continue article >>

|

A friend of Pandosy wrote: “The first trees

planted by the missionary produced a beautiful apple, deep red, shaped like

a Delicious – a good winter apple.” Pandosy’s orchards

eventually established the Okanagan Valley as one of Canada’s chief

fruit-growing areas.

Pandosy was a devout pastor who also served his flock

as doctor; teacher; lawyer; orator; botanist; agriculturist; musician

(he played the French horn); voice instructor; and sports coach. He

fast became known as a troubleshooter, a peacemaker, a defender of justice,

a champion of the underdog – and, above all else, a great

humanitarian.

But Pandosy was not your typical priest. Once, when his

young Indian interpreter and guide gambled away Pandosy’s brand new

saddle, Pandosy immediately challenged him to a fight.

Love and respect for his priest kept the native

man’s hands down by his side, causing Pandosy to grab the culprit by

the scruff of the neck and demand that he put up his fists and defend

himself. Pandosy, however, tripped on his cassock, allowing his opponent to

jump on top of him.

Those who observed the spectacle were surprised at

Pandosy’s unpriestly behaviour. Dusting himself off, Pandosy

thundered: “I’m not mad at him, I’m mad about the

saddle.”

Pandosy, who experienced other missions throughout

British Columbia – Esquimalt, Fort Rupert, Fort St. James, the

lower Fraser, Stuart Lake, Mission City and New Westminster – was

among those who believed that Indians and their culture should be

respected, and that the ways of the white man were largely responsible for

the indifference that many Indians displayed toward Christianity.

He wrote to a superior in the 1850s: “But I

shiver, Reverend Father, when I think of the miserable state of the

Savages, as I cannot delude myself, at least in the country where we live,

the Savages around us are what the Whites have made them and what we have

let them become instead of working hard and generously to make them

otherwise with the help of the grace of God.”

On February 6, 1891, Father Pandosy died near

Penticton, after a pastoral visit during cold weather to Keremeos. His body

was brought to the mission that he had founded on the site of present-day

Kelowna, and lovingly laid to rest.

Pandosy influenced whites and natives alike and saved

the lives of thousands during the various wars between natives and

settlers. He taught that two cultures and two worlds could live together

peacefully based on mutual trust and respect.

Pandosy’s life of faith and sacrifice are

evidenced by the missions he founded and so diligently served. On his own

behalf he said, “I expend myself and over this is spent God’s

grace.”

Ted Gerk is director of

operations at Heritage Christian Online School in Kelowna.

October 2008

|