|

By David F. Dawes

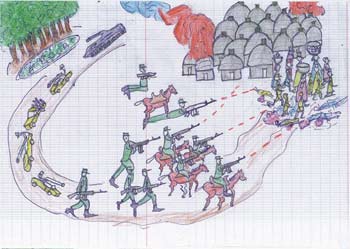

THE IMAGES bear all the hallmarks of typical

children’s art: bold use of colours; disregard for perspective; crude

but charming likenesses of buildings, animals and people.

But some of the people are bleeding; others are

shooting them. Welcome to the world of Darfur’s children.

These images are part of an exhibition titled

‘The World Must Know: Children of Darfur Speak.’ They are the

dramatic centre of a December 10 event at Vancouver’s Jewish

Community Centre, featuring four speakers: former Secretary of State David

Kilgour; a survivor of the Darfur conflict; Holocaust survivor Bob Waisman;

and Anna Schmitt, affiliated with Waging Peace Canada.

Schmitt, who attends a local Anglican church, collected

the children’s art while doing research in Darfur. She told BCCN how she obtained the

images. “It was not that difficult. I was interviewing the men and

women. One woman said: ‘You should speak to the children, if you want

to know the truth.’” She decided to do so, and went to the

children with a simple request.

“I wanted them to share in writing.”

However, “one boy said, ‘May we draw?’” Art, she

soon learned, “is their way of expressing themselves.” While

some gave written accounts, most created pictures. She collected some 500

drawings – “mostly Darfur children in camps in eastern Chad,

and some Chadian kids.” “I wanted them to share in writing.”

However, “one boy said, ‘May we draw?’” Art, she

soon learned, “is their way of expressing themselves.” While

some gave written accounts, most created pictures. She collected some 500

drawings – “mostly Darfur children in camps in eastern Chad,

and some Chadian kids.”

The frankness of the images had an immediate

impact on her.

“You can imagine, I was quite shocked. Their

drawings were quite telling; 98 percent of them were about attacks. I had

to control my emotions. I’m a mother. To see these images from small

children . . . . I had to choke back tears. No child should have to carry

around such memories.”

Despite the emotional power of the images, she strove

to approach the project logically.

“I wanted to make sure it was their own

testimony, not a collective memory. So I talked to individual children

about their drawings, to confirm the details. I spoke to approximately

two-thirds of the 500.”

The drawings are part of the case being made against

the government of Sudan at the International Criminal Court.

“Supporting evidence is probably too strong a

term” for the images, Schmitt said. Rather, the drawings were a means

of “weaving a picture” of Darfur’s strife.

Court officials, she said, are using the drawings

rather than testimony, because they “don’t want to subject the

children to re-opening their wounds.”

Continue article >>

|

| |

| A Darfur child's vision of atrocities perpetrated by 'devils on horses.' |

The alleged perpetrators of those wounds, known

as ‘Janjaweed,’

have yet to be apprehended. “Janjaweed means ‘devils on horses,’” said Schmitt.

“They are mercenaries paid and armed by the

Sudanese government; but the government denies any involvement.” Many

of the drawings, she said, depict both mercenaries and Sudanese military

personnel committing atrocities.

The janjaweed, she contended, “are brainwashed that this is a jihad [‘holy war’];

they are doing it for Allah.” However, she noted a tragic irony:

“Most of the victims are Muslims.”

Increased attention on the situation, she said, has had

some effect. “As long as we have our eye on them, a full-fledged

attack may be prevented.” But the measures which have been taken so

far, she said, are inadequate.

A United Nations resolution was proposed, which would

have made Darfur a ‘no-fly zone,’ and disarmed the janjaweed. The Sudanese

government objected to these conditions; they also stipulated that no

Western nations be involved in the UN operation. The government, she

maintained, has been “stalling” the UN.

A Hybrid Force, combining UN and African Union

troops has been proposed, and is scheduled to go to Darfur early next year.

They will be able to protect civilians, but not respond to any attacks with

force. Consequently, she contended, the Hybrid Force is “a tiger

without teeth. I think they should have the power to disarm the janjaweed.”

Schmitt is not entirely pessimistic. “I do see

hope – if the Western governments have the political will to do

something.” Failing that, she maintained, “this is on its way

to becoming another Rwanda. It’s a slow ethnic cleansing – a

slow genocide.”

While her faith has sustained her in this endeavour,

she said she had not initially sought to do this kind of work for God.

“I didn’t go looking for it; it came looking for me. I

was pretty naive about what was going on in Darfur.

“I was reminded of the work of Brother Andrew,

and of how Dutch people helped hide Jews during World War II. It

seemed the Lord was putting this in front of me.”

Aside from the difficulty of the task, she was daunted

by the response of some fellow believers. “Some in the

Christian community, at one time, opposed my work; but now they

don’t. At first, they couldn’t understand why I would put

myself in harm’s way.”

The work will likely get more intense. “My

promise to the children was to give them a voice.” The next step, she

said, will be to provide a similar platform for some of the adult victims

– specifically, “the women, many of whom have suffered from

rape.”

Contact: www.wpcanada.org

December 2007

|