|

By Peter T. Chattaway

LAST YEAR, many Christians went out of their way to

caution their fellow believers against over-reacting to the movie version

of The Da Vinci Code. LAST YEAR, many Christians went out of their way to

caution their fellow believers against over-reacting to the movie version

of The Da Vinci Code.

Yes, the film put forth a deeply problematic view of

Jesus and church history; but instead of protesting against it, Christians

were encouraged to see it, discuss it with their friends and, in general,

‘engage’ with it as part of their broader engagement with the

culture.

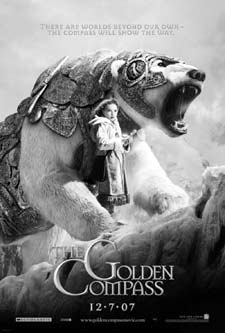

This year, however, many Christians have begun to raise

the alarm over the movie version of The Golden

Compass, which comes out December 7. They have

sent each other emails full of warnings about the

‘anti-religious’ books on which the film is based. They have

pointed their friends to websites that describe some of the story’s

objectionable content. And there has been little, if any, talk of

‘engagement.’

| |

| Stars of The Golden Compass: Dakota Blue Richards as Lyra |

What changed between last year and this? What is

different about this movie?

Well, for one thing, Compass, which is the first part of an award-winning trilogy by

Philip Pullman known collectively as His Dark

Materials (the other

two books are The Subtle Knife and The Amber Spyglass) has been marketed as a children’s fantasy –

whereas The Da Vinci Code was ostensibly for adults.

For another, Compass – which was so hugely successful in its native England

that the trilogy has already been dramatized on the radio and on stage

there – never became a household word in North America, so many

Christians are only just hearing about it now for the first time. They did

not have time to resign themselves to the inevitability of the movie as

they did with The Da Vinci Code.

Decrepit angel

Most significantly, though, whereas Da Vinci author Dan Brown at least paid

lip service to God, Jesus and spirituality, however poorly understood, Compass is the first part of

a trilogy which depicts the God of the Bible as a lying, decrepit angel

whose death is brought about by two heroic children.

The trilogy also depicts the afterlife as an awful,

dreary place, set up by God to keep spirits trapped, and so the two

children find a way to let these spirits escape – by disintegrating.

Oblivion, rather than eternal life, is the happy ending here.

And finally, the story climaxes with a re-enactment of

the Fall, in which the two children discover the pleasures of love and

listen attentively as an ex-nun explains to them that “the Christian

religion is a very powerful and convincing mistake, that’s

all.”

Meanwhile, in the real world, author Pullman has made

no secret of how he detests the implicitly Christian stories of C.S. Lewis,

of how he wants to set up a “Republic of Heaven” without any

sort of kingdom or king, and how he feels “a slight revulsion”

whenever he hears the words “spiritual” or

“spirituality.”

So if concerned parents are worried that this latest

fantasy blockbuster is part of a broader ‘attack’ against the

faith, and that the story was written to poison children’s minds

against the biblical God . . . well, there is certainly some basis for

that.

The filmmakers, however, have gone out of their way to

allay such fears.

Continue article >>

|

| |

| Nicole Kidman as the evil Mrs. Coulter |

Dumbed down

The studio, New Line Cinema – which also produced

the delightful Lord of the Rings trilogy as well as the explicitly Christian film The Nativity Story – says it

has made the book’s supernatural elements more generic, kind of like

‘the Force’ in Star Wars. A different studio similarly dumbed

down the Chronicles of Narnia movie, turning the Deep Magic into a vague, mystical thing

which guides Aslan’s ‘destiny.’

Even Pullman, who sometimes expresses great joy in

slamming religious beliefs, has begun to publicize the film among liberal

Christians such as Donna Freitas, co-author of Killing

the Imposter God (Jossey-Bass), who claims the Materials trilogy is a

“Christian classic” because it replaces the

“medieval” old-man-in-the-sky concept of God with what she

considers a more mystical, “panentheistic” view of the divine.

There is no space to explain her argument in detail.

Suffice it to say that, in the books, the spirits which disintegrate leave

their particles behind, and Freitas regards those particles as a divine

force which fills the world.

However, efforts to downplay the story’s

anti-religious themes have only annoyed the trilogy’s more secularist

fans.

And so writer-director Chris Weitz, whose previous

credits include American Pie and About a Boy, recently told the MTV Movies Blog that, if he gets to make the sequels, he will preserve

the story’s more “iconoclastic” elements – which

are much more pronounced in those books anyway.

In the interview, Weitz admitted that he had watered

down some elements from the first book; but he said he had to do this in

order to “popularize this series of extraordinary books and open them

to a wider reading public than ever before.”

If the first movie is a hit, then the studio will go

ahead with the sequels – and then, said Weitz, he will be able to dig

into the more controversial stuff.

“The whole point, to me, of ensuring that The Golden Compass is a

financial success is so that we have a solid foundation on which to deliver

a faithful, more literal adaptation of the second and third books,”

he said.

“This is important: whereas The Golden Compass had to be

introduced to the public carefully, the religious themes in the second and

third books can’t be minimized without destroying the spirit of these

books.”

Agenda

In the light of such comments, it is tempting to say

that there really is an ‘agenda’ behind The Golden Compass. But that is no

reason to avoid ‘engaging’ with this film, the same way we

might with any other. Pullman is a powerful writer with a vivid

imagination, and one of the reasons his books are so popular is because he

sometimes, despite himself, articulates some very important truths.

Some children, and even some adults, may not be ready

to handle Pullman’s books or the movies based on them.

But for a fuller exploration of these issues, those who

are ready should check out books like Tony Watkins’ Dark Matter (IVP) and Kurt Bruner

& Jim Ware’s Shedding Light on His

Dark Materials (Tyndale), both of which are

fine examples of how to appreciate problematic art even as one critiques

it.

For my part, I thought the book version of The Golden Compass was one of the

most creative, delightful and suspenseful stories I had read in recent

memory; but I cringed at some of the more hateful or dismissive passages in

the sequels.

So I hope this first movie is great – and I hope

it flops.

December 2007

|