|

BCCN’s series of faith profiles marking the

150th anniversary of the founding of B.C. concludes, with the story of one

of the province’s key missionaries. Taken from Canada: Portraits of Faith (Reel to

Real), edited by Michael Clarke. BCCN’s series of faith profiles marking the

150th anniversary of the founding of B.C. concludes, with the story of one

of the province’s key missionaries. Taken from Canada: Portraits of Faith (Reel to

Real), edited by Michael Clarke.

By Peter Murray

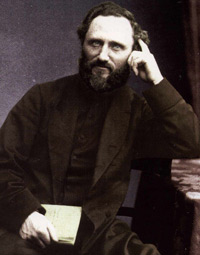

OF ALL the European missionaries who came to Canada in

the 19th century to convert aboriginals, few had more impact than William

Duncan.

For 60 years, Duncan was the controversial leader in a

movement that would bring far-reaching cultural and economic change to the

Indians.

Born in 1832 in the rural Yorkshire hamlet of Bishop

Burton, Duncan’s background was humble. His mother was a servant girl

and his father unknown. His grandparents brought him up in nearby Beverley,

where – after winning acclaim as a boy soprano in the cathedral

choir – he came under the influence of Reverend Anthony Carr.

The pastor recruited Duncan to teach Sunday school, and

became the missing father figure in William’s life. From Carr, he

absorbed the evangelical views he held all his life.

Duncan became successful as a wholesale leather

merchant. However, his life irrevocably changed when he went to a church

meeting and heard a speaker urging young men to join the Anglicans’

Church Missionary Society (CMS).

“Well, that is a new idea,” Duncan later

recalled thinking at the time. “Before I left the room, I felt very

inclined to it. And I woke up that night and thought . . . what good is

wealth? . . . But if I can go and do good somewhere, that will be something

worthwhile.”

He trained for two and a half years at the CMS school

at Highbury College in north London. He studied school organization and

teaching, and some theology and medicine.

Upon graduating, Duncan boarded a Royal Navy ship bound

for Victoria, British Columbia. He arrived October 1, 1857 at Fort Simpson,

a Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) trading post between the mouths of the

Skeena and Nass Rivers, just north of present-day Prince Rupert.

Duncan set to work immediately with the energy and

diligence that became the hallmarks of his career. He visited all the

Indian houses surrounding the fort stockade, where the 29 Tsimshian tribes

had gathered to trade with the HBC and with each other.

Duncan next undertook the difficult task of learning

their language, a step urged by Henry Venn, the secretary of the CMS, who

set the society’s policy from 1841 until his death in 1873. Duncan

also enlisted the natives’ help in building a schoolhouse adjacent to

their village.

Although Duncan attempted to follow most of

Venn’s instructions, in some ways he went against Venn’s

wishes. He argued, with some justification, that by being on the scene he

could judge how to adapt Indian ways better than anyone like Venn in

faraway London could.

Venn wanted the missionaries to work with native

chiefs; but Duncan met considerable opposition from tribal leaders, who

considered him a threat to their power and prestige as he gained converts

to Christianity. This conflict was one of the reasons that he, along with

70 supporters, established a new community away from the fort.

The site chosen was Metlakatla, the former winter home

of the Tsimshians who had moved to Fort Simpson. It offered more room and

better land, including spacious beaches for pulling up canoes. There would

also be relief from the drunkenness and violence surrounding the fort.

And so, in spring 1862 the move was made. After

drawing up a list of rules to govern Metlakatla, Duncan set to work with

prodigious effort to turn it into a model Indian community.

He did his best to turn his followers into good

Victorian workingmen – dressing them in English clothes, putting them

in houses resembling English cottages and creating a native police force.

He set up a store, bought a trading schooner, established a sawmill and

held workshops to make rope and nets.

Continue article >>

|

The population of the new townsite increased rapidly,

as other natives fled Fort Simpson because of a major smallpox epidemic

that had spread up the coast from Victoria.

Duncan was able to save many lives with his rudimentary

medical training and a supply of vaccine, thus weakening the power of the

tribal medicine men and gaining a credibility that attracted new converts.

Duncan supervised the construction of a 1,200-seat

church, the largest on the coast north of San Francisco. He also taught the

Tsimshians such trades as weaving, coopering (barrel making) and printing.

They were also encouraged to continue their traditional occupations of

hunting and fishing – the latter assisted by Duncan building a

large salmon cannery.

By the mid-1870s, the fame of Metlakatla had spread

widely, and it was used in England to gain support for the missionary

cause. Both the provincial and Dominion governments sought Duncan’s

advice on matters affecting the Indians, especially land title issues.

Over the next decade, however, the little

community’s population had increased to 1,000, and it was wracked by

discord. Most was the result of Duncan’s feud with Anglican officials

and with Henry Venn’s successors in London, who were taking the CMS

away from Venn’s pragmatic policies.

Despite constant CMS and church pressure, Duncan

declined ordination and so was unable to administer some church functions,

which were left to visiting clergy or other ordained missionaries. Duncan,

however, blocked even them from administering mass, as he was well aware of

Indian cannibalism rituals and feared the ceremony would be misunderstood.

Unlike other missionaries who measured their success by their number of

baptisms, Duncan withheld baptism until he was convinced the applicants

were ready to receive it.

In 1887, Duncan departed Metlakatla to set up a new

mission on Annette Island in Alaska. Most of the Indians sided with Duncan,

and 800 accompanied him to create yet another successful industrial mission

village, New Metlakatla, where he died in 1918.

Duncan’s critics point to his almost dictatorial

control over the Tsimshians, and his emphasis on business and secular

affairs. Nonetheless, his compassion for the natives – whose

lives had been upturned by cultural change – is unquestioned, as is

the love and respect the majority accorded him.

He had begun his ministry among the natives critical of

their ways, but over time he took a more positive and enlightened attitude

toward their culture and most of its artifacts. One modern scholar

described Duncan as “a daring, determined social reformer who was a

century ahead of his time.”

Peter Murray is author of The

Devil and Mr. Duncan.

December 2008

|