|

By Mark Buchanan

THE WORLD is not dying for another article about rest.

But it is dying

for the rest of God.

I certainly was. I became a Sabbath-keeper the

hard way: either that, or die. Not die literally, but die in other ways.

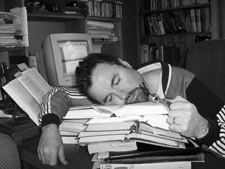

It happened subtly, over time; but I noticed at some

point that the harder I worked, the less I accomplished. I was often a

whirligig of motion.

My days were intricately fitted together like the old

game of Mousetrap – every piece precariously connected to every

other, the things needing to work together for it to work at all. But there

was little joy, and stunted fruit. My days were intricately fitted together like the old

game of Mousetrap – every piece precariously connected to every

other, the things needing to work together for it to work at all. But there

was little joy, and stunted fruit.

To justify myself, I’d tell others I was gripped

by a magnificent obsession, I was purpose-driven. It may have begun that

way. It wasn’t that way any longer.

Often I was just obsessed, merely driven, no

magnificence or purposefulness about it. I once went 40 days – an

ominously biblical number – without taking a single day off. And was

proud of it.

But things weren’t right. Through my work often

consumed me, I was losing my pleasure in it – and many other things

besides – and losing, too, my effectiveness in it. And here’s a

secret: for all my busyness, I was increasingly slothful.

I could wile away hours at a time in a masquerade of

working, a pantomime of toil – fiddling about on the computer,

leafing through old magazines, chatting up people in the hallways. But I

was squandering time, not redeeming it.

And whenever I stepped out for a vacation, I did just

that: vacated, evacuated, spilled myself empty. I folded in on myself like

a tent suddenly bereft of stakes and ropes and poles, clapped hard by the

wind. The air went out of me.

The inmost places suffered most. I was losing

perspective. Fissures in my character worked themselves into cracks. Some

widened into ruptures.

I grew easily irritable, paranoid, bitter,

self-righteous, gloomy. I was often argumentative: I preferred rightness to

intimacy. I avoided and I withdrew.

I had a few people I confided in, but few friends. I

didn’t understand friendship. I had a habit of turning people, good

people who genuinely cared for me, into extensions of myself: still water

for me to gaze at the way Narcissus did, dark caves for me to boom my voice

into and bask in the echoes. I didn’t let anyone get too near. And

then I came to my senses.

I wish I could say this happened in a dazzling vision

– a voice from heaven, a light that blinded and wounded and healed

– but it didn’t. It was more like a slow dawning.

I didn’t lose my marriage, or family, or

ministry, or health. I didn’t wallow in pigmuck, scavenging for husks

and rinds. But it became clear that, if I continued in the way I was

heading, I was going to do lasting damage.

And it became obvious that the pace and scale of my

striving were paying diminishing returns. My drivenness was doing no one

any favours. I couldn’t keep it up and had no good excuse to try.

I learned to keep Sabbath in the crucible of breaking

it.

God made us from dust. We’re never too far from

our origins. The apostle Paul says we’re only clay pots – dust

mixed with water, passed through fire. Hard, yes, but brittle too. Knowing

this, God gave us the gift of Sabbath – not just as a day, but as an

orientation, of seeing and knowing.

Continue article >>

|

Sabbath-keeping is a form of mending. It’s mortar

in the joints. Keep Sabbath, or else break too easily, and oversoon. Keep

it, otherwise our dustiness consumes us, becomes us, and we end up able to

hold exactly nothing.

In a culture where busyness is a fetish, stillness is

laziness. But without it, we miss the rest of God.

Stillness invites us to enter more fully so that we

might know him more deeply. “Be still, and know that I am God.”

Some knowing is never pursued, only received. And for that, you need to be

still.

Sabbath is both a day and an attitude to nurture such

stillness. It is both time on a calendar and a disposition of the heart. It

is a day we enter, but just as much a way we see. Sabbath imparts the rest

of God: the things of God’s nature and presence which we miss in our

busyness.

You might have grown up legalistic about Sabbath

– your principle memory of it is of stiff collars chafing at the neck

and a vast, stern silence that settled on the house like a grief. I hope to

invite you out of that rigidity and gloom.

You might have grown up indifferent about Sabbath. To

you, it is a musty, creaky thing about which only ancient rabbis and old

German Mennonites bother.

You tend to see Sabbath as something archaic and

arcane. Something from which you’re exempt. Something that, like

bloomers and corsets and top hats, went out of style long ago.

I hope to convince you that Sabbath, in the long run,

is as essential to your well-being as food and water, and as good as a wood

fire on a cold day. I hope to tune your ears to better hear, and gladly

accept, Jesus’ invitation: “Come to me, all who are weary and

heavy-laden, and I will give you rest.”

When I use the word Sabbath I mean two things.

First, I mean a day, the seventh day in particular. I

want to convince you that setting apart an entire day for feasting

and resting and worship and play is a gift and not a burden – and

neglecting the gift too long will make your soul, like soil never left

fallow, hard and dry and spent.

But when I say Sabbath I also mean an attitude. It is

perspective, and orientation. I mean a Sabbath heart, not just a Sabbath

day.

A Sabbath heart is restful even in the midst of unrest

and upheaval. It is attentive to the presence of God and others even in the

welter of much coming and going, rising and falling. It is still, and knows

God – even when mountains fall into the sea.

You’ll never enter the Sabbath day without a

Sabbath heart.

Reprinted by permission: ‘The Rest of God, Mark Buchanan, 2006, W.

Publishing, a division of Thomas Nelson, Inc., Nashville, Tennessee. All

rights reserved.’ Mark Buchanan is pastor of New Life Community

Baptist Church in Duncan.

October 2008

|